Good intentions but the right approach? The case of ACEs

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events that children can be exposed to while growing up. These include the direct impact of suffering abuse or neglect, or the indirect effects of living in a household affected by domestic violence, substance misuse or mental illness. The original ACEs study found that those with a higher number of ACEs were more likely to have physical and mental health difficulties and to engage in health-related risk-taking behaviours than those with less traumatic childhoods. In the 20 years since the study was published the ‘ACEs movement’ has steadily expanded, particularly in the United States.

It took much longer for the first UK ACEs study to be published and it is only really in the last few years that awareness of ACEs has grown on these shores. England is currently lagging behind Wales and Scotland in recognising ACEs in national policy, though many local areas are developing their own ACEs strategies.

I only heard about ACEs two or three years ago. I was aware of each of the individual experiences that the authors had termed ACEs, but not of their being grouped together and counted. There was something about the idea that nagged away at me right from the start, but I couldn’t articulate it. Then I came across a concrete example of good intentions causing harm in a charity I was working alongside. The organisation helps vulnerable people with a range of problems, from domestic violence to involvement with the criminal justice system. Staff had received training on ‘ACE-awareness’ and how to incorporate routine enquiry about ACEs into their work with service users, apparently to offer more tailored support. Many of the staff had faced the same issues as those they were now trying to help, and several reported finding the training distressing. They were told of the potential damage ACEs can cause, which caused them to worry about the impact it had had on themselves. Several reported feeling guilty about having ‘passed on’ their own ACEs to their children. They were taught all about the (potential) negative impacts of ACEs, but offered no reassurance that you can have a high number of ACEs and still be totally fine. I posted this issue in an online ACES forum and found that it was not an uncommon issue. I’ve since worked on various ACEs projects and think my thoughts are finally just about lined up enough to write down.

There are of course lots of examples of fine work going on around ACEs, but there are also aspects of the ACE movement that make me feel a little uncomfortable. I worry that what is clearly a well-intentioned desire to just do something might not do good and could cause harm. My concerns below are absolutely not meant as a criticism of the motivation and altruism underlying the ACEs movement, but as a cautionary nudge to make sure that, in our enthusiasm to do good, we don’t run before we can walk.

A narrow definition of adversity

The original ACEs study defined ten kinds of adverse experience; five that involved direct harm to a child (physical, sexual and emotional abuse; physical and emotional neglect) and five that affect the environment in which they grow up (domestic violence; substance abuse; mental illness; parental separation; incarceration of a household member). My first thought on reading the paper was – why just these? What about bullying? Hunger? Homelessness? The death of a parent? And why only things that happen within the household, surely community violence is an adverse experience? Since the initial study, a great many others have been published that include one or more of these or other ‘extra’ ACEs. To me this illustrates that, outside of academic research, a focus solely on the ten ‘official’ ACEs was always too narrow.

The ACE movement also seems to conflate adversity with trauma, and the two are very different. In this article, Gary Walsh states that

the term risks suggesting that adversity of any kind is bad or traumatic. While abuse and neglect should always be considered fundamentally wrong, traumatic and preventable, the same cannot always be said for adversity. Everyone will experience adversity at some point and there is often strength and hope to be found in it. Our responses to adversity can nurture resilience and loving relationships while also defining our identities

ACE-awareness

In a way, I think the ACEs movement has become a victim of its own success. It’s in danger of becoming its own distinct field, rather than what I think it should have been: another, powerful piece of evidence to raise awareness of and advocate for what we already knew to be important. It has done that to some extent, of course, but unfortunately it has spawned a distinct campaign that has raised awareness primarily of the ten, narrowly-defined ACEs chosen by the original researchers. The ACEs study provided some excellent population-level data, but I don’t believe it was ground-breaking research. I know to some that might seem blasphemous, but it will not have come as a surprise to anyone that traumatic experiences occurring early in a child’s life can have a lasting impact.

Being ‘ACE-aware’ has become somewhat of a badge of honour. We now have ACE-aware schools, councils, businesses, even an ACE-aware nation. But awareness without action achieves nothing. There is a world of difference between ACE-awareness and trauma-informed practice. The former can mean different things to different people but may mean as little as having heard of ACEs and that they can be harmful. That’s great, but useless on its own. I’m aware of heart surgery, but that doesn’t qualify me to advise a triple bypass. There are of course many examples of people or organisations who rightly see becoming ACE-aware as just one piece of the jigsaw that is effective and comprehensive trauma-informed practice, but plenty of others who believe ACE-awareness is an end in itself; and that can be dangerous, as my earlier example demonstrates.

Medicalisation

There is a great deal of published literature asserting that ACEs can have tangible effects on the biology of individuals. This is powerful stuff and has really helped to raise awareness of ACEs because, rightly or wrongly (well, wrongly), issues are often only taken seriously if they can be labelled as a medical problem or considered a disease. The ACEs movement in the States was, initially at least, led by medics, and that is probably one of the reasons it gained traction.

But… if you think about it, why does it matter if ACEs have demonstrable biological effects? Why does that make the case more powerful? In their submission to the House of Commons Science and Technology Select Committee Inquiry into the evidence-base for early years intervention, Edwards et al. asked what I thought was a really pertinent question:

Would a life lived in the miserable conditions created by adverse situations be wrong even if there were no long-lasting biological effects?

Of course it would. So, while the evidence demonstrating that ACEs have a biological impact has been important in raising awareness, there is a danger that ACEs become yet another example of what is essentially a social issue with societal solutions being labelled as a medical one. When that happens, the focus shifts to identifying and ‘treating’ individuals, rather than prevention at the population level.

Individualism

Time and time again we see the approach to tackling complex social problems focus on searching for ‘solutions’ at an individual level. What that means is that rather than making the necessary but difficult changes to society that would reduce the risk of rubbish stuff happening , we wait for the rubbish stuff to happen then try to mitigate its effect – what Geoffrey Rose called “a targeted rescue operation for vulnerable individuals”. For ACEs, that means that the approach has tended to rely on finding individuals with a high ‘ACE score’ and then trying to help them (a bit more on the ACE score and that assumption of needing help later). It’s a natural and intuitive approach to medicine, but we also know from Rose that, on its own, it has little effect at the population level. For pretty much any disease or negative outcome you can think of, the greatest burden will fall on the vast majority of people considered as low-risk, simply because of their greater numbers:

If we want to prevent ACEs and their consequences at a large scale, then a population approach where we shift the level of risk in the entire population is required. For that we need to prevent the causes of ACEs, and not only act on those individuals already affected. Really, of course, we need to both offer targeted help to those that need it and reduce the level of risk in the whole population (Rose called these the ‘high risk’ and ‘population’ strategies, respectively). But we’re all skint because of funding cuts, and we can’t do both. We’re forced to choose between helping those in most pressing need or incrementally improving population health. In that situation, the former always wins. But what a shame we’re forced to choose.

ACE scores, screening and ‘routine enquiry’

The ACE score (i.e. the number of ACEs an individual has experienced) was designed for population-level epidemiological research. It was not intended to inform practice at the individual level. In their final report, the Science and Technology Committee explicitly state that “the simplicity of [the ACEs] framework and the non-deterministic impact of ACEs mean that it should not be used to guide the support offered to specific individuals.”

Demonstrating an association (note association, not cause) between high numbers of ACEs and poor outcomes at the population level tells us precisely nothing about any individual with a high ACE score. It is absolutely possible to have ten ACEs and be totally fine, or to have no ACEs and be a gibbering wreck (I’m proof of that). It is the very definition of an ecological fallacy, yet many advocate its use as a screening tool.

A short while ago I attended a meeting for an organisation who were conducting some research into the experiences of young people involved with the youth justice service. When they passed around the questionnaire they’d been using, I was shocked to see they were asking questions about ACEs. To children. When I asked why they were asking them, they were unsure. They had no plan for what to do with the information and hadn’t thought about whether it might be upsetting. The questionnaire was being administered by an 18 year old girl with no training. Luckily, following advice from myself and others, they removed these questions.

There was absolutely no malice in what they were doing of course, they were acting with the best intentions and, well, being ACE-aware I suppose. But any form of screening has the potential to do more harm than good and we “shouldn’t let good intentions undermine […] screening principles”. Screening for ACEs risks labelling individuals who are otherwise content and well and basically fine, or signposting them to services they don’t need. Or, perhaps worse, highlighting issues that need urgently addressing, but not knowing how to. This paper by David Finkelhor cautions against prematurely screening for ACEs and is a must-read. He states that we don’t yet have any evidence-based interventions for high ACE scores and we don’t understand the potential negative outcomes and costs of screening:

if general ACE screening were to result in a big increase in unnecessary and inherently expensive child welfare referrals and investigations as one of its main outcomes, we might look back on the ACE mobilization as a disastrous distraction to the development of evidence based child welfare policy

I’ve also come across advocates for ‘Routine Enquiry for Adversity in Childhood’. “It’s not screening!”, they say. It is screening. There is no evidence it has a positive effect on outcomes. When I’ve raised this I’ve been pointed to evaluations like this as evidence. In fact, this one states that:

- None of the sites successfully implemented the REACh program

- “One of the underlying assumptions […] is that the enquiry process itself may be therapeutic” but that “practitioners raised concerns that this may not be the case”

- “Concerns were expressed around the ethics of identifying ACEs without the ability to offer appropriate support to those who may need it”

- “Little evidence currently exists on the value of routine enquiry about childhood adversity, using the ACE (or equivalent) questionnaire, or the responses or interventions required for those reporting childhood adversities”

So not really evidence of effectiveness, then… and yet it’s been rolled out across several services in England, including the charity I spoke of in my example earlier.

ACEs as a cause

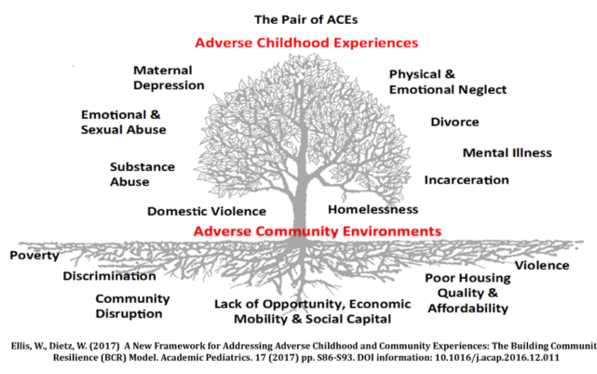

There is no doubt a strong correlation between ACEs and negative outcomes in later life, but that does not necessarily demonstrate causation (see Correlation and causation in the Committee report). I think of ACEs as a symptom of an underlying cause: shit life syndrome, basically. I think this is illustrated well by the Building Community Resilience (BCR) ‘pair of ACEs’ framework:

The Pair of ACEs Tree demonstrates the interconnectedness of wider social circumstances and adverse experiences within the family environment. The leaves on the tree represent the ‘symptoms’ that are easily recognized in clinical, educational and social service settings, but the underlying causes are the usual suspects: a lack of affordable and safe housing, community violence, inequality, discrimination, poverty, etc..

If generally difficult lives (or ‘adverse socioeconomic circumstances’) are the root cause of ACEs, then I’m not sure we even need distinct ACEs prevention strategies; it’s the same as preventing everything else. What we need is the funding and freedom to develop broad prevention approaches that focus upstream. A living wage. Clean streets. Good, affordable housing. Parks. Stuff for teenagers to do. Welfare. Jobs. Childcare. Good schools. Of course, we could never prevent everything, so we will always need access to excellent individual support. But that is not going to reduce the incidence of ACEs. Trauma-informed practice and proper help for individuals is absolutely essential, but it’s not really prevention is it? We need to tackle the roots of the problem too.

Summary

I’ve banged on for ages here, so I want to just reiterate that I know there are many hundreds of people and organisations doing excellent, holistic work on ACEs and adversity in childhood more generally, and that much of what I’ve written will not be new or relevant to them.

But I have witnessed practices being adopted that aren’t (at least yet) based on evidence, but rather the very human desire to ‘just do something’ to alleviate a perceived injustice. Public health is an evidence-based discipline, but we are all human. We will at times be guilty of picking evidence to suit our own narrative, even unconsciously and with the best intentions. If something seems important, we may choose to do it quickly rather than do it properly. It’s not just ACEs of course: Making Every Contact Count, social prescribing, apps… all being rolled out without robust evidence, all ignoring the underlying, upstream factors to a greater or lesser extent. It’s something we need to be a little wary of more generally and be careful not to run before we can walk. ACEs are no doubt an important advocacy tool that reflect deeper, underlying problems; but we must not lose sight of the bigger context and wider determinants of public health issues.

Other critiques of ACEs

For summary of other useul ACEs critiques, see this Twitter thread I put together with Gary Walsh

Yes!! I wrote basically the same article a little bit ago – great minds think alike. I’m glad to see more people raising awareness around this. https://unconditionallearning.org/2018/01/02/letting-go-of-aces-to-support-trauma-affected-students/

Ah, great – yep, very similar points!

Glad to read about your concerns about this – I work in a field in which we will surely expect to see more about ACEs arising.

But what are the types of population interventions you seem to hope for? Something I find so frustrating about work on e.g. inequality is that authors and researchers often seem so fastidious about their findings proving that this specific measurement X seems to correlate and be linked to this other event Y… conclusion? “Reduce inequality”. That simple!

We surely didn’t need any new work on ACEs to know that a child growing up in a household of substance abusers is a bad thing! But I find myself frustrated with handwringing reports (not this piece) that add yet more drops to the ocean of research showing that complex social problems are bad.

I completely agree that we need to be aware of the felt need to “do something” without perhaps the necessary supporting evidence. I’m just not quite sure what the alternative is.

Thanks for your comment. There are loads of ways to improve your inequality actually, and lots of published works showing what is effective and what isn’t… A good place to start is what Michael Marmot calls ‘proportionate universalism’, which is basically doing stuff that benefits everybody, but targeting more resources at populations that are more in need.

Thanks for a great, thought-provoking article. You hit on many of the points those of us working on early adversity find concerning about the entire ACEs phenom. I would caution, though, that there are plenty of people who do NOT accept that abuse, neglect, etc. in childhood has any valid connection to later poor health/well-being outcomes. Many people strongly adhere to the “stop complaining and get over it,” idea. In other words, if your childhood experiences do cause you problems later in life, that is due to laziness, a character defect or some other fault of your own.

And because of these ideas that remain very strongly rooted in society, I would also caution that your “weak and gibbering” comment is demeaning and inappropriate. It plays into those very stereotypes.

An otherwise great article, though. Thank you.

Thanks Kathy, glad you found it useful. I take your point but it was myself I was calling a gibbering wreck, in a more light-hearted way than perhaps it came across to you. Just an example of how anybody can have issues even with a happy childhood like mine… just as it’s possible to have a difficult childhood and be fine – nothing is necessarily deterministic.

Sorry, that should be “gibbering wreck,” not “weak and gibbering.”

Thank you.

We have signed up to Reach pilot and I am so sceptical.

You have put into words why.

Where is this Lynne?

“I know to some that might seem blasphemous, but it will not have come as a surprise to anyone that traumatic experiences occurring early in a child’s life can have a lasting impact”

Let me take you back to what started the ACEs research, Dr Vincent Filetti screening morbidly obese people prior to bariatric surgery. He found that once he asked about sexual abuse, 55% of patients disclosed this. Morbid obesity is something still assumed by most of the public and large tranches of the medical profession to be caused by gluttony, a lack of will-power, laziness and poor diet (and therefore to be the fault of the individual and as legitimate a reason as smoking to deny them various healthcare interventions, and to be a reasonable reason for mockery) was in fact often a symptom of huge unresolved trauma. Having met people who have wanted to make themselves ugly or asexual with fat, or bigger/heavier than an abuser, or to have a shield deeper than a knife is long, this was really helpful to me because it gave robust evidence to confirm the anecdotal examples that these physical symptoms can reflect psychological injuries. The ACEs studies then went on to prove that these “social” adversities have profound impacts on public health, and made a clear economic case for addressing the determinants of health.

So whilst I’m with you that counting ACEs at the individual level isn’t usually helpful, that increased risk of negative outcomes should never be presented as making things inevitable, and that making people “ACE aware” is not helpful unless they know with (and are resourced to address) the distress that they uncover, I would consider that the concept of ACEs and the findings from the studies are amongst the most profoundly important scientific findings in my lifetime.

Anyway, I’ve written more here: https://clinpsyeye.blog/2019/03/25/the-misrepresentation-of-evidence/

Thanks you this is great, you have articulated what I have been thinking and feeling about rolling out ACE screening. I now feel more confident to express my views to others.

Thanks Alison, glad it was useful

Hi Andrew,

I appreciate your thoughtful article and comments and your TREE!! I’ve come here following the twitter and FB threads and am glad to learn of your work.

I never understood trauma until I left medicine (I was a family doc who also did obstetrics), retrained as a somatic psychotherapist and began to learn how subtle and broad it is.

I’ve spent the past 20 years looking at and integrating existing research and learning if and how it helps make sense of chronic disease (and many other issues above but disease has been my own area of focus).

I’ve learned about how exposure to adversity (such as the ACEs and the other things you mention like bullying etc) and to missing experiences (premature birth or cesarean birth for example, where a baby doesn’t get full exposure to the support of the womb or the pressure and flora of the vaginal canal) influence the developing organs, nervous system – immune system etc; it also affects cell danger response, as well as gene function through epigenetics and more.

I completely agree we need to make changes at the roots and through public health. Safety, sufficient funds/ resources / support are critical – but they aren’t enough for many to recover from effects of adversity on behavior, physical and emotional health, ability to sustain intimate and meaningful personal relationships, and more – and that’s where many tools for healing trauma effects come in.

You mention in an ACEs Connection comment in your post there that “, I’m just yet to find evidence that the ten ACEs together or alone are of any more significance than countless other stressful life experiences.”

I agree. I think ACEs are just the tip of the iceberg.

This is what I’ve been exploring for two decades years now.

I have a chronic illness for which there is no treatment or cure. I also have an ACE score of 0. Understanding the big pic of how all kinds of different types of adversity influence health makes all the difference – for coping but also for healing – because as you express, the 10 ACEs are just a tiny tip of the iceberg.

Those who are already affected need tools while public health and medicine changes policies – which may take a long time. And many tools actually do exist. We need many more studies – but there are people whose work is repeatable and that helps people heal symptoms of many different kinds. It’s just a tiny start – but the evidence is growing.

Also, Felitti describes that understanding ACEs and having a medical doctor acknowledge its effects often itself provides validation and relief to patients. If you’ve read Donna Jackson Nakazawa’s book you also see how it helped her find tools to improve from her multiple autoimmune and other diseases.

Pediatricians introducing ACE screening in their practices have found, to their surprise, that most parents appreciated learning there is something they can do to help their kids. And that there ARE ways of doing this without blame – even as there is a huge risk that doctors – in particular – and others in general will use ACEs inappropriately and incorrectly (such as in the examples you mention).

I invite you to read one of my blog posts about some of the science I never knew as an MD – whether one on ACEs and chronic illness, or one on how healing effects of adverse babyhood events for a mother can help heal her child’s asthma, one on the mechanisms explaining the links, or my story of how understanding adversity makes sense of disease.

Here’s a post on how healing ABEs can improve or cure asthma in kids (and could help prevent many diseases or identify early risk to help repair inevitable exposures we have to adversity simply because we are human).

https://chronicillnesstraumastudies.com/causes-of-chronic-illness-risk-factors-for-asthma/

Hi: We are running a consensus survey on ACEs with support from RAND and Accent and would be very pleased if you could participate. If you are interested, please respond with your e-mail address and I will ask RAND to sent you the link.

Interesting post, Andy.

Came across it while looked for balanced counter views to ACe for a paper I’m working on (Uni psychology assignment),

This article (below)* I wrote a bit back might interest you and your readers. As well of obviously considering ACE, it looked at it’s polar opposites, namely PCE’s (Positive Children Experiences) and BCE’s (Benevolent Childhood Experiences).

The research suggests that is you have a high ACE, but also a high PCE, things balance out, so the net effect of the ACE is much lower. Arguably, of course, if your ACE is low, but your PCE is also low to nothing, well, the door swings both ways, so the negative effects of your otherwise decent ACE are magnified.

*Childhood programming

https://ackadia.com/health/psychology/childhood-programming/

Just reading your article on ACE’s as part of my Pre-registration Nursing Programme and it is so refreshing to read! And very important.

I had not heard of ACE’s before, and I have worked in healthcare for the past 20 years. I was very curious as I began to read as I could relate to a lot of these ACE’s, but yet I have gone on to lead a happy and fulfilling life with a wonderful husband and 2 children.

This article has highlighted exactly what I was thinking as I read about ACE’s, is there something wrong with me? Am I a traumatised individual? Thank you so much Andrew Turner for this, as I said very important.

Thank you!